Has Contemporary Environmentalism Failed the Environment?

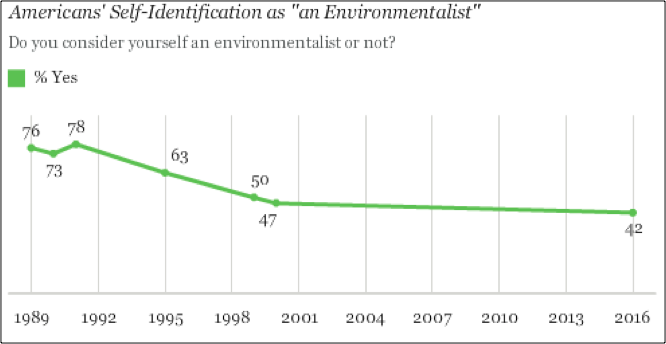

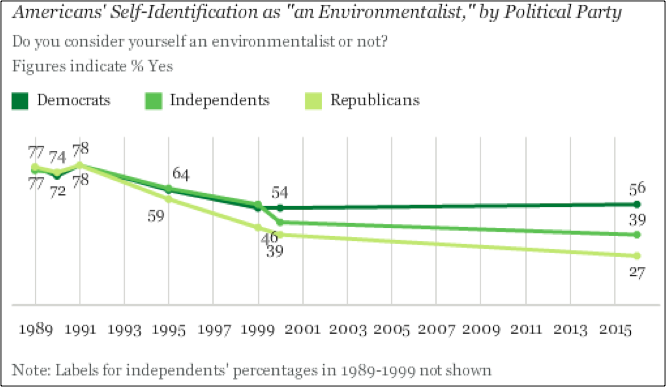

It would be hard to imagine a time when nearly four out of every five Americans would declare themselves to be environmentalists. And it would be even harder to fathom that same figure applied to both Democrats and Republicans. Yet this was the case less than three decades ago.

A recent Gallup poll found 42 percent of Americans would identify themselves as environmentalists today, down from 78 percent in 1991. Additionally, when broken down by party affiliation, only 27 percent of Republicans consider themselves environmentalists versus 56 percent of Democrats. Compare that to 1991 when Americans of both parties shared the same high percentage of 78 percent.

Subscribe to Receive Insights

"*" indicates required fields

So what’s changed in the last 25 years? Some of the general decline can be attributed to the tangibility of environmental problems. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, combatting important problems — like the deterioration of the ozone layer and cross-regional air pollution leading to acid rain — mobilized national and international support for solutions because people could see the environmental damage happening right in front of their eyes. Under Republican administrations, policymakers from both parties worked together to ratify the Montreal Protocol and pass amendments to the Clean Air Act. The reality of today’s marquee environmental issue, climate change, is that most Americans do not see its negative effects on a daily basis.

There’s also an inverse relationship between Americans’ concerns about the economy and concerns about basically everything else. In times of prosperity, Americans feel the freedom to worry about a variety of issues. Yet when the country enters a period of economic uncertainty and discontent, many other issues fall away.

Yet those reasons don’t explain the growing party gap in identifying with environmentalism. It may be fair to fault a variety of stakeholders on all sides. But one can’t ignore that there has been a major evolution where environmentalism has become ideological rather than rational.

The result is the environmental movement being perceived as just another special interest. A number of organizations leading the charge on environmental issues have transformed into partisan political machines as opposed to being issue-based, results-oriented advocates. These groups seem to take greater pleasure — and raise more money — out of simply attacking their opponents instead of seeking actual solutions.

Regardless of your stance on the science of climate change, it is undeniable that many environmental groups who claim to be advocate for a solution on this issue have ceased to persuade the public and instead have engaged in the politics of shame against those who disagree with them. This trend within environmentalism is vividly illustrated in the New York State Attorney General’s investigation into Exxon for allegedly misleading to the public regarding the risks of climate change. While many environmental groups have touted this investigation, few point out the simple fact that it achieves nothing in the effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions while offending those who believe such political speech is Constitutionally protected.

This is how contemporary environmentalism is failing the environment. Gallup argues, “While dwindling identification of the public as environmentalists may not be a welcome development for supporters of the environmental movement, it may not reflect a substantial weakening of the movement and its ability to achieve its objectives.” Yet it’s actually their objectives that have changed. Many environmental groups have shifted from promoting solutions to simply serving as political vehicles to admonish those they perceive to be their enemies. What would better serve our environment and our climate would be laying the groundwork for a bipartisan path to generate thoughtful consensus on policy.

Make no mistake: there is space for bipartisan compromise on these issues. Look no further than the recent bipartisan work on energy reform legislation backing clean energy sources like nuclear and hydropower. And there’s the recent creation the bipartisan House Climate Solutions Caucus, aiming to find solutions a broad spectrum of Americans can get behind to confront global warming. The question at hand is whether contemporary environmentalism once again can be inclusive and solutions-oriented.

I’ve been involved in partisan politics and I’ve had experience in energy and environmental policymaking debates. From that experience, I’ve learned partisan politics itself isn’t the culprit; it plays a very important role in our democracy. From my observations, if those who truly strive for smart clean energy policy want Americans to stop thinking of environmentalism as a four-letter word, they should be wary of anyone who uses environmentalism as a veil for their own political agenda.